November 12, 2021

November 12, 2021 Parenting

Parenting 0

0

Remember the ending to The Wizard of Oz, when Glenda the good Witch asks Dorothy what she had learned in her journey. Dorothy says, “I suppose I learned that when you wish and wish for your heart’s desire but you can’t find it, then maybe it’s in your own back yard and you ever really lost it to begin with.”

The ideas that many parents want their children to embrace – ideas such as cooperation, kindness, or honesty – may be the most challenging concepts for parents to get across. In a flicker, youngsters spot a lecture coming and are quick to mentally retreat, leaving behind a black expression that nearly every parent recognizes with a sigh.

Fortunately, “in their own back yard,” parents already have a strategy that is fully capable of effectively delivering these messages to ready and open ears. I invite you to rediscover a secret weapon that you have always had – and youngsters have always responded to – the Story.

An Ancient Treasure

In these days of “virtual-this” and “electronic-that,” there are those who might relegate storytelling to the dusty realm of a bygone era. Yet storytelling remains strongly rooted in our human cultural experience after all those years. We see it surface in many forms. From advertisers’ sales pitches, to speeches delivered by public figures, to the fervent promise of broadcasters for “More on that story after our commercial break…”

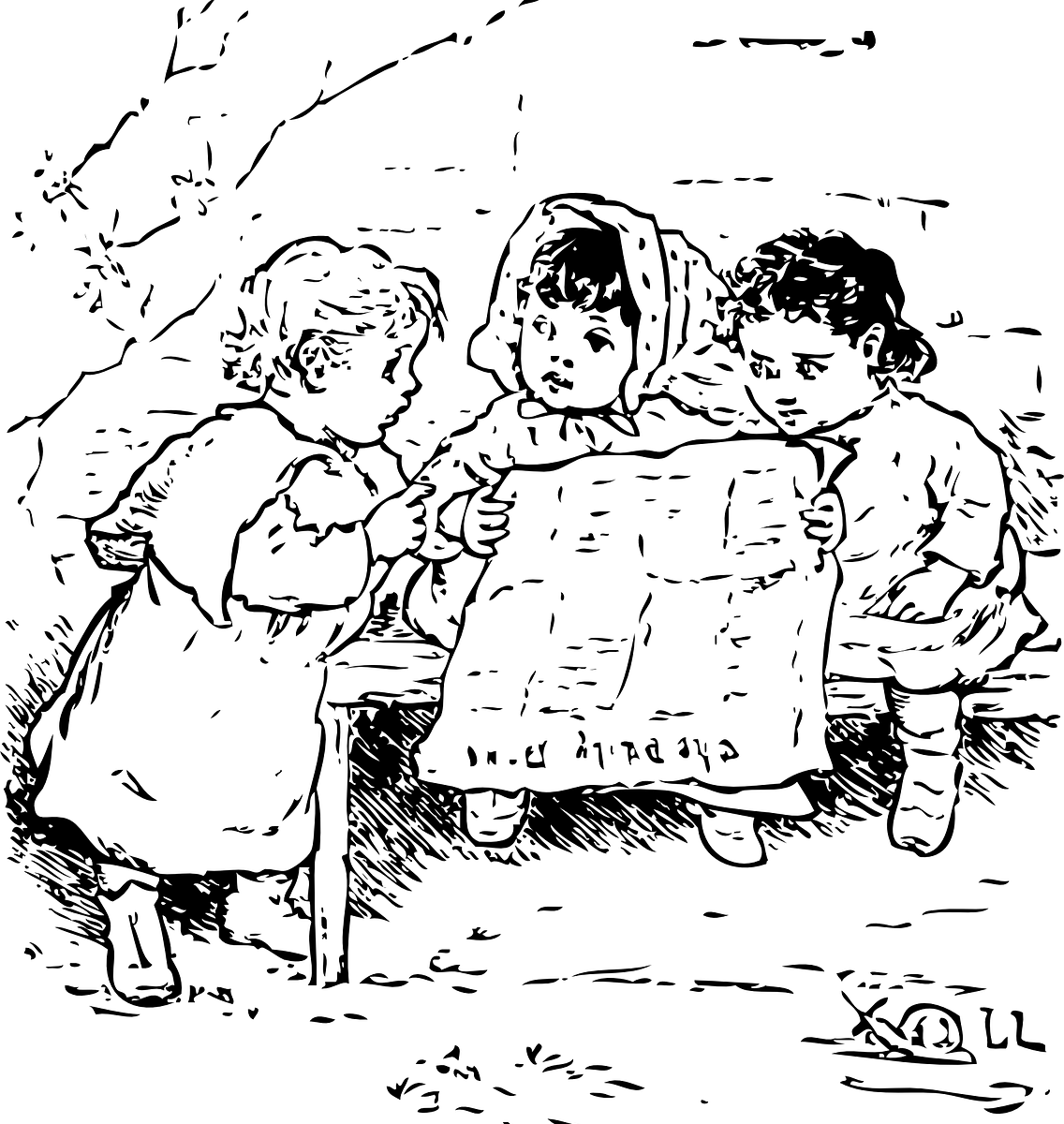

Among children, however, storytelling holds even a stronger and deeper magic. Indeed, it appears that children demand stories with the same insistence as they hunger for attention or food!

Transfixed by Stories

Parents worldwide will attest to the phenomenon that is children and stories. The magical opening, “Once upon a time…” or “Many years ago…” will focus young eyes which, just a moment ago, had been aimlessly darting along the ceiling. Event casual openings such as, “Here’s a story I heard today you might like…” or “Did you hear the story about…?” bring dangling and impatient feet to freeze mid-swing. A child engrossed by the travels of an errant fruit fly turns his or her full attention to the teller of the tale. The sense of concentration is palpable.

As a Girl Scout leader, I was once transporting a station wagon full of shockingly raucous 6-year-old Brownies. Three times I stopped the car to reprimand the miscreants for fighting, yellow, throwing, hitting. All to no avail. At a loss, I slid in a CD of fairytales. Instantly, the entire carload quieted. The would-be hooligans remained utterly still until the completion of the story, at which point they almost instantly burst into mischief again. The next story began and, once again, a hush replaced the bedlam.

Why is the attention of children captivated by stories? For one thing, the pattern of stories (a beginning-middle-end) sets up a structure that children recognize and understand. The end is sure to be satisfying – the triumph of the youngest of three children, the tackling of impossible tasks, the glory of a troubled romance set right. Such popular themes in fairytales demonstrate to children, as Bruno Bettleheim says in his classic study The Uses of Enchantment, “that a struggle against severe difficulties in life is unavoidable” but that if one meets the hardships, one will “master all obstacles and at the end emerge victorious.”

Indeed, children seem to respond well to any story offering magic or fantasy, perhaps because, being young, they live more closely to the outer worlds of magic and fantasy themselves. When my older daughter was 4½ years old, she had started the morning with a small hole in her pants that by the end of the day was exposing most of her knee. “That hole is getting so big,” I warned her, “soon you’re going to fall right down into it.” “You’re joking!” she said with a chuckle, and then looked squarely at me – “right?” As children enter elementary school, their personal sense of time and place sharpens, but the world of magic and storyland beckons at the borders.

Contemporary stories from modern life can also capture powerful claims on a child’s heart when the story features the child, family members, friends, or other people the child knows. Openings such as, “Did I tell you the story about your wild Grandpa Louis, who threw the whole town into a panic when…” or “I’ll never forget what happened when you were just learning to walk and…” also rivet a child’s attention because of the personalized nature of the tale.

Add to all of the factors the experience of hearing a story – that is, the voice of a storyteller, the impact of direct eye contact, the entertaining quality of hand gestures, facial expressions, ad-libs, and dramatic reactions to events in the story, and it’s not surprising that children are mesmerized by stories.

The plain fact that stories reliably capture the attention of children creates a unique and significant opportunity for parents. Whereas youngsters often respond reluctantly if not outright rebelliously to direct parental instructions on how to behave, those same children will welcome and absorb the very same ideas when interwoven through a story.

As a parent, which scenario do you prefer? To relate instructions to a child whose expression dares, “Whatever-you’re-selling-I’m-not-buying-it!” Or to offer those same instructions to a child whose expression says, “Really? Tell me more. Now.”

While we can agree that stories are a powerful conduit, it’s also clear that in and of themselves, stories do not necessarily deliver positive messages. In fact, stories can just as easily deliver negative messages, and often do. Imagine that a story is a form of transportation, a kind of express vehicle. Its contents may be fresh crispy apples, or its contents may be cartons of explosives. The contents that are loaded onto the “storytelling express at the outset of its journey will determine what’s received at its destination. As a parent, your role is to load worthwhile messages onto your storytelling express and send it to its destination – the heart of your child.